Geography & Buildings

With the advent of Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1832, and Britain's support of the independence movement in the previous decade, the Peloponnesus opened up to tourists and researchers alike. With routes that took them inland from Messina and Corinth, they left detailed accounts of the Lykaian remains in the 19th Century.

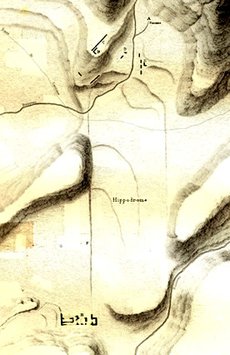

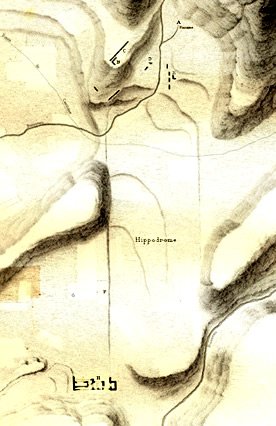

Hippodrome, Charles Ernest Beulé

The stadium is situated on the north-east side on Lykaion: when one arrives there by slopes covered with a fine grass, one sees that the mountain has been fertilized only by the work of man. It was the king Lycaon who instituted the Lykaian Games, to entice his errant subjects by the games and render the captivity of their villages more mild. These games were the most ancient in Greece, after those of Olympus: Saturn and Jupiter fought there for the prize in wrestling before the creation of the human race. We don’t know, how they used to celebrate, nor if they were always in honor, despite their curious location and the difficulty in surrendering there. Nonwithstanding, according to the ruins that one finds there and which offer Hellenic stones of the belle époque close to some cyclopean debris, one cannot doubt their long duration and the care one would take, in a time of less decline, to decorate one’s theater.

These stones appeared at the head of the stadium, toward the semi-circular area where the judges, magistrates, and prominent citizens sat. As for the two sides of the stadium, one can recognize them without trouble; since the earth was left in their place, and the gravel pit preserves its shape. There is a great plateau leaned against the mountain from three sides, open from the fourth; through that opening, the view glides to an immense height on the summits of the north of Arcadia and on part of the plain. The only detail which has been transmitted to us on the Lykaian games, is that after the crowning of the victors, the young ones, nude, would follow with bursts of laughter those they spotted on their path. Wouldn’t one call this the origin of the Roman Lupercalia? Titus Livius affirms, in effect, that this custom was carried over by Evander.

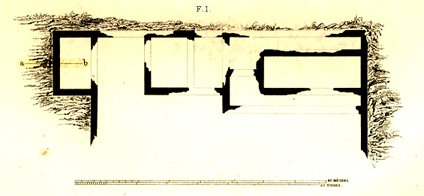

The small stadium, about which Pausanias speaks, is upward of the great stadium and falls perpendicularly on its edge. Only the shape, and some stones half-recovered by the earth, makes it recognizable. Above the great stadium, to the right, was the temple to Pan, who presided over the games here which were consecrated to him. The stones are partly buried, or stacked in a manner to leave nothing to distinguish. They are admirably trimmed, level, similar, and elegant. This temple, besides being very small, adjoined a grove.

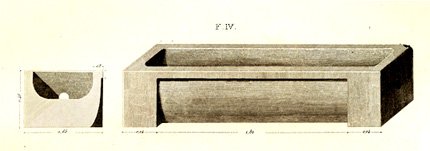

On the opposite side, the Hagno fountain flowed and still flows, where the priest of Jupiter came to exorcise drought. After the customary sacrifices and the supplications, he touched the surface of the water with an oak branch, without pushing it in there: the water thus touched, a light vapor rose which quickly formed a cloud, it drew other clouds and spilled itself over Arcadia in a healthy rain.

Hagno was one of three Nymph wet-nurses of Jupiter, according to the Arcadians, who wanted the king of the gods to be raised on Lykaion, in a line called Cretea. The resemblance of this word to the name of Crete was caused, they said, by an error of other Greeks. It was the constant preoccupation of the Arcadians to link the origin and history of men and gods to their land. Also, they called Lykaian Olympus, the sacred summit, the birthplace of their religion and their society.

There, everything conspired to inspire respect and fear in mortals. There was a great enclosure consecrated to Jupiter, into which entrance was prohibited to men. Those who entered there in disregard of the law would inevitably die within the year. Moreover, and it was not at this less terrible, one knew that everything was alive, if one placed a foot there, he would immediately lose his shadow. How much belief did hunters hold makes a point, when the ferocious beasts they stalked sought refuge there!

Moreover, the cult of Lykaian Jupiter didn’t need these stories to arouse a mysterious terror in the imagination of the people. On the the highest summit of the mountain, there was a plateau, an altar, where human blood often ran, in honor of the divine heir of cruel Saturn. Hence in nearly all of the Peloponnesus one finds oneself and one believes oneself to be nearer the sky than the land. Before the altar and toward the east, two columns bear two golden eagles which the sun hits each morning with its first rays. A grandiose hypothesis, which recalls the temple of Apollo on the summit of Taygetis, the altar of Raining Jupiter on Hymettus. Certainly, a simple heap of earth so-placed has more majesty than the most magnificent temple.

Supported by the clouds, surrounded by infinite space, covered by the eternal ether, didn’t it seem to touch the feet of an invisible god? And didn’t mortals sense his breath pass across their faces? Why would monstrous babarity mar such a great idea? Why did these columns, whence one can view all Arcadia, recall less the power of the god than the suffering of men? One cannot precisely say when these human sacrifices ended, which the Arcadians brought to Italy, and which reestablished themselves in Rome until the Second Punic War. The words of Pausanias pretended, not that they lasted to his time still, but that one substituted there some repulsive ceremony which was a symbol of it:

“Today” he says, “one offers on this altar secret sacrifices to Jupiter. It hardly pleased me to be informed of the manner in which things happen there; that they remain thus like they are and like they were to one in the beginning.”French

Le Stade est situé sur le versant nord-est du Lycée: on y arrive par des pentes couvertes d’une herbe fine, on voit que la montagne a été fertilisée jadis par le travail de l’homme. Ce fut le roi Lycaon qui institua les jeux lycéens, pour attirer par des fêtes ses sujets errants et leur render plus douce la captivité des villes, nouvelle pour eux. Ces jeux étaient les plus anciens de la Grèce, après ceux d’Olympie: Saturne et Jupiter y disputèrent le prix de la lutte avant la creation de genre humain. Nous ne savons, ni comment ils se célébraient, ni s’ils furent toujours en honneur, malgré leur singulière situation et la difficulté de s’y render. Cependant, d’après les ruines qu’on y trouve et qui offrent des pierres helléniques de la belle époque à côtés de quelques debris cyclopéens, on ne peut douter de leur longues durée et du soin qu’on prit, dans un temps moins reculé, d’embellir leur théâtre.

Ces pierres se voient à la tête du stade, vers la partie demi-circlaire où siégeaient les juges, les magistrats et les citoyens considérables. Quant aux deux côtés du Stade on les reconnaît sans peine; car les terres sont restées à leur place, et la carrière a conservé sa forme. C’est un grand plateau adossé à la montagne de trois côtés, ouvert du quatrième; par cette ouverture, la vue plane d’une immense hauteur sur les sommets du nord de l‘Arcadie et sur une partie de la plaine. Le seul detail qui nous ait été transmis sur les jeux lycéens, c’est qu’après le couronnement des vainqueurs, les jeunes gens nus poursuivaient avec des éclats de rire ceux qu’ils recontraient sur leur chemin. Ne dirait-on pas l’origine des Luoercales des Romains? Tite-Live affirme, en effet, que cette cotume avait été apportée par Évandre.

Le petit stade, dont parle Pausanias, est en avant du grand stade et tombe perpendiculairement sur son extrémité. Sa forme seule, et quelques pierres à demi recouvertes par le sol, le font reconnaître. Au-dessus du grand stade, à droite, était le temple de Pan, qui de là présidait aux jeux qui lui étaient consacrés. Les pierres sont enterrées en partie, ou entassées de manière à ne rien laisser distinguer. Elles sont admirablement taillées, plates, éntendues, élégantes. Ce temple, du reste fort petit, était adosse à un bois.

De côté opposé, coulait et coule encore la fontaine Hagno, où le prêtre de Jupiter venait conjurer la sécheresse. Après les sacrifices et les prières d’usage, il touchait avec une branche de chêne la surface de l’eau, sans l’y enfoncer: sur l’eau ainsi émue, s’élevait une vapeur légère qui bientôt formait un nuage, attirait d’autres nuages et se répandait sur l’Arcadie en pluie salutaire.

Hagno était une de trois nymphes nourrices de Jupiter, d’après les Arcadiens, qui voulaient que le roi des dieux eût été élevé sur le Lycée, dans un lien appelé Crétea. La ressemblance de ce mot avec le nom de la Crète avait causé, disaient-ils, l’erreur des autres Grecs. C’était la préoccupation constante des Arcadiens de rattacher à leur patrie l’origine et l’histoire des hommes et des dieux. Aussi appelaient-ils le Lycée Olypme, Sommet sacré, le berceau de leur religion et de leur société.

Là, tout concourait à inspirer aux mortels le respect et la terreur. Il y avait une grande enceinte consacrée à Jupiter, dont l’entrée était interdite aux hommes. Celui qui y pénétrait au mépris de la loi mourait infaillablement dans l’année. De plus, et ne n’était pas une chose moins terrible, on savait que tout être animé, s’il y posait le pied, perdait immédiatement son ombre. Com bien de fois les chasseurs n’avaient-ils pas fait cette remarque, quand les bêtes féroces qu’ils poursuivaient y cherchaient un refuge!

Le culte de Jupiter Lycéen n’avait pas besoin, du reste, de ces fables pour frapper l’imagination des peuples d’un mystérieux effroi. Sur le sommet le plus élevé de la montagne, il y avait un tertre, un autel, où le sang humain avait coulé souvent, en l’honneur du dieu héritier du cruel Saturne. De là se découvre presque tout le Péloponèse, et l’on se croit plus près du ciel que de la terre. Devant l’autel et vers l’Orient, deux colones portaient deux aigles dorés que le soleil frappait chaque matin de ses premiers rayons. Idée grandiose, qui rapelle le temple d’Apollon sur le sommet du Taygète, l’autel de Jupiter pluvieux sur l’Hymette. Certes, un simple amas de terre ainsi placé avait plus de majesté que le temple le plus magnifique.

Soutenu par les nuages, entouré de l’espace infini, couvert par l’éternel Éther, ne semblait-il pas toucher les pieds du dieu invisible. Et les mortels ne sentaient-ils pas son souffle passer sur leurs fronts? Pourquoi une barbarie monstrueuse souilla-t-elle une si belle idée? Pourquoi ces colonnes, que l’on vouyait de toute l’Arcadie, rappelaient-elles moins la puissance du dieu que la souffrance des hommes? On ne dit point quand finirent ces sacrifices humains, que les Arcadiens portèrent en Italie, et qui se renouvelèrent à Rome jusqu’à la seconde querre punique. Les paroles de Pausanias feraient croire, non pas qu’ils duraient encore de son temps, mais qu’on y avait substitué quelque cérémonie repoussante qui en était le symbole:

“Aujourd’hui,” dit-il, “on offre sur cet autel des sacrifices secrets à Jupiter. Il ne me plaisait guère de m’informer de la manière dont les choses s’y passaient; qu’elles restent donc comme elles sont et commes elles on été dès le commencement.”

Beulé, Charles Ernest. Études sur le Péloponè. Paris: Firmin Didot frères, 1855. 129ff.